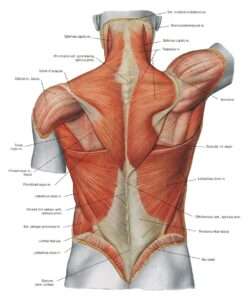

ZWhat are the “Crunches” felt in Muscles during a Massage?

During my career as a Massage Therapist, I have been asked dozens of times, “What is that crunchy feeling in my muscles?” My clients know that there is no perfect answer as we literally would need to look inside your body via x-ray, CT scan, MRI or ultrasound to view the area in pain, and assess its condition. Now, I will attempt to bring to light several possibilities of what the crunchy structures are in your muscle tissue and for the purpose of this blog, I will be talking about skeletal muscle only. In this article, I need to look at a few subjects that deal with muscle movement, soft tissue structures and metabolic processes to set a foundation, so please bear with me.

Let’s take a look at Lactic Acid. What is it and how does it affect our muscles?

Lactic acid is a byproduct produced by your body during the metabolic process of glycolysis, or when your body turns glucose into energy. Lactic acid is then broken down into lactate, an action that releases hydrogen ions into the blood. Lactic acid is essentially a carbohydrate within cellular metabolism and its levels rise with increased metabolism during exercise and with catecholamine (hormones made by your adrenal glands, are released into the body in response to physical or emotional stress. The main types of catecholamines are dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine/adrenaline) stimulation.

In the past, people have blamed lactic acid for muscle soreness. However, newer evidence finds that lactic acid actually provides another fuel (carbohydrate) source for working muscles.

High Intensity and low intensity exercises – what’s the difference?

By training at a high intensity (lactate threshold training), the body creates additional proteins that help absorb and convert lactic acid to energy. There is an even rate of lactic acid production and blood lactate removal at rest and under low-intensity exercise.

energy. There is an even rate of lactic acid production and blood lactate removal at rest and under low-intensity exercise.

As your intensity of exercise increases, the imbalance causes a buildup in blood lactate levels, which is how the lactate threshold is reached. At this lactate threshold, blood flow decreases, and fast-twitch motor ability increases. This peak level of performance is referred to as lactate threshold training.

A low lactate threshold (LT) means we produce lactate at low exercise intensity. If our LT is reached at low exercise intensity, it often means that we do not have adequate concentrations of the enzymes necessary to oxidize pyruvate (end-product of glycolysis derived from additional sources in the cellular cytoplasm, and is ultimately destined for transport into mitochondria as a master fuel input undergirding citric acid cycle carbon flux) at high rates.

DOMS (Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness)

Research suggests that delayed onset muscle soreness aka DOMS is from microscopic tears and trauma resulting from physical exertion, not lactic acid buildup. DOMS is muscle pain that begins typically a day or two after you’ve worked out. Pain felt during or immediately after a workout is called acute muscle soreness.

Research suggests that delayed onset muscle soreness aka DOMS is from microscopic tears and trauma resulting from physical exertion, not lactic acid buildup. DOMS is muscle pain that begins typically a day or two after you’ve worked out. Pain felt during or immediately after a workout is called acute muscle soreness.

Acute muscle soreness is that burning sensation you feel in a muscle during a workout due to a quick buildup of the buildup of metabolites (primary metabolites are ethanol, glutamic acid, aspartic acid, acetic acid, lactic acid, glycerol. secondary metabolites are pigments, resins, terpenes, alkaloids, antibiotics, peptides, growth hormones) during intense exercise. Acute muscle soreness typically dissipates shortly after you stop the exercise.

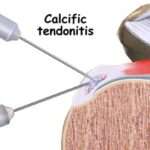

Calcification – what is it and can I avoid it?

Calcification of soft tissue (arteries, cartilage, tendons, heart valves) can be caused by a vitamin K2 deficiency or by poor calcium absorption due to a high calcium/vitamin D ratio. This can occur with or without a mineral imbalance and not by an excess of calcium in your diet. Mineral deficiencies, pH imbalances, and enzyme deficiency also contribute to calcified, or fibrotic soft tissues. Basically, abnormal accumulation of calcium salts in body tissue(s) is the definition of calcification.

Calcification occurs when calcium accumulates in body tissue, blood vessels, or organs. These calcium deposits can interrupt many of your body’s normal functions and cause pain. Since calcium is transported via the bloodstream, calcium deposits can end up in almost any area of the body.

If the deposits end up in soft body tissues such as breasts, muscles, and fat, the condition is known as soft tissue calcification. Soft tissue calcification can occur as a result of injury or as an inflammatory reaction triggered by infection, trauma, repetitive motion, or autoimmune illness. It can also be caused by a condition known as hypercalcemia, which is characterized by high levels of calcium in the blood.

Soft tissue calcification can seriously affect the quality of your life if the calcium deposits become too large or are found in an area that disrupts organ function or activities of daily life such as walking or sports activities.

What is Crepitus and how does it affect muscle function?

Crepitus, sometimes called crepitation, describes any grinding, creaking, cracking, grating, crunching, or popping that occurs when moving a joint. People can experience crepitus at any age, but it becomes more common as people age. The sound associated with crepitus may be muffled or it may be loud enough for other people to hear. The term crepitus is sometimes also used to describe other conditions, such as lungs crackling from respiratory illnesses and bones grating after fractures.

Causes of crepitus are:

- air bubbles popping in the fluid of the joints.

- the rubbing of hard tissues (bone on bone).

- damaged, eroded, or rough cartilage.

- the air inside soft tissues of the body.

- tendons or ligaments snapping over the joint’s bone structure.

Your tendons are a strong piece of connective tissue that attach your muscles to bones. Sometimes, calcium deposits build up in this area, and this excess calcium is known as calcific tendonitis. For some people, this may not cause any significant health issues or damage, but for others, it can cause excessive pain and restrict muscle movement. The most common area that seems to be affected is the group of rotator cuff muscles, which are located in the shoulder.

Crepitus usually is not a cause for concern. In fact, most people’s joints crack or pop occasionally, and that is considered normal. But if crepitus is regular and is accompanied by pain, swelling, or other concerning symptoms, it may be an indication of arthritis or another medical condition.

- aponeurotic fascia — which is thicker and separates more easily from muscles

- epimysia fascia — which is thinner and more tightly connected to muscles

Visceral fascia. Layer goes around certain organs that settle into your body’s open spaces, including the lungs, heart, and stomach.

Parietal fascia. Tissues that line a body cavity are called parietal fascia. For example, your pelvis is lined by parietal fascia.

- A lifestyle without enough physical activity

- Activity that uses the same part of your body over and over

- Surgery or injury that causes damage to one part of your body

So what does all of this have to do with the hard, crunchy nuggets in my back?

In essence, those hard nodules are indicative of toughened, even calcified, tendons or dried-out facia layers, that are overused, overstretched, or damaged with repeated injury. The toughened material that forms at the muscle attachment, develops over time to repair the damaged tissue in most cases. Alternatively, scar tissue may be formed which is a thick, fibrous tissues that take the place of healthy ones that have been damaged from a cut, disease, significant, or repeated injury, or surgery. Tissue damage may also form internally, so scar tissue can form post-surgery.

In essence, those hard nodules are indicative of toughened, even calcified, tendons or dried-out facia layers, that are overused, overstretched, or damaged with repeated injury. The toughened material that forms at the muscle attachment, develops over time to repair the damaged tissue in most cases. Alternatively, scar tissue may be formed which is a thick, fibrous tissues that take the place of healthy ones that have been damaged from a cut, disease, significant, or repeated injury, or surgery. Tissue damage may also form internally, so scar tissue can form post-surgery.

The body uses many different materials, enzymes, water, etc. to keep your muscles, joints and major organ systems running at peak performance. Healthy muscle movement by our peripheral portion of the central nervous system (CNS) controls the skeletal muscles. Keeping your nervous system healthy is a great way to keep the muscles, attachments, and organs healthy. Proper diet and nutrition gives your body a leg-up on potential disease and disfunction.

If you suffer from any of these issues, massage has been proven to significantly reduce pain and increase positive blood flow to areas of concern.

While massage does not fix broken tendons or mend injuries, it can help by:

- increasing skin and muscle temperature.

- increasing blood and lymphatic flow.

- allowing more parasympathetic activity.

- relieving of muscle tension and stiffness.

- reducing muscle pain, soreness and DOMS.

- increasing joint range of motion.

- increased psychophysiological responses ie. relaxation, better mood and fatigue reduction.

(Weerapong et al., 2005). (Morelli et al., 1999). (Hemmings et al., 2000).